Jaroslav Vonka, a Rediscovery in Bronze: Three Rare Sculptures, a Family Odyssey, and the Master of Wrocław Metalwork

When three small bronzes surfaced from a single American collection—two inherited directly through an émigré family and a third found years later by pure chance—they brought with them a century of European history. The figures are now confidently attributed to Jaroslav Vonka (1875–1952), the Czech-born master of artistic blacksmithing whose expressive iron and bronze works helped define the look of modern Wrocław (then Breslau). Their journey—from a scholar’s workshop milieu in Central Europe, through war and exile, to an auction catalog—traces not only the arc of a rare artist’s output, but the endurance of one family that safeguarded its cultural memory across continents.

This article introduces three Vonka bronzes entering our sale—two from family descent and one from an independent rediscovery—sets out the case for the attribution, and situates them within Vonka’s life and achievement. It also documents, with the family’s permission, the extraordinary provenance of the two inherited pieces, a narrative that intersects with the Kindertransport, Theresienstadt, and the postwar academic life of the mathematician Wolfgang Heinrich Johannes Fuchs at Cornell University.

The Sculptures Entering the Sale

Jaroslav Vonka, Cubist Bronze Soldier, Wrocław, c. 1925

A stylized soldier rendered with planar, angular masses—an emblem of Vonka’s language at the threshold of Cubism and Art Deco.

Jaroslav Vonka, Cubist Bronze Figure, Wrocław, c. 1925

A companion figure with the same fracturing of planes and taut silhouette that Vonka brought to his wrought-iron gates and architectural reliefs.

Jaroslav Vonka, Kneeling Figure with Spyglass, c. 1920s (Receipt 1116-3)

The kneeling pose and instrument (a spyglass) telegraph a poetic image of watchfulness and horizon-seeking—modernist in form, allegorical in spirit.

For the kneeling figure, the consignor adds an important note: the family retains the original cast (not for sale); this second cast came to light years later on the open market, innocently listed as a “vintage man with a spyglass” by a seller in Germany who had no idea of the artist’s identity. That mislabel, and the later scholarly update, tell you everything about Vonka’s current market visibility: widely admired in Poland and Czechia within architectural history and museum circles, yet still under-recognized—and very sparsely represented—on the international auction circuit.

From “Wonka/Wanka” to Vonka: Solving the Attribution

The path to attribution began with a memory fragment: the family recalled a name sounding like “Wonka” or “Wanka.” A brute-force search through databases under those spellings led nowhere. The break came from stylistic analysis—the planes, facets, and compacted anatomy pointed to the prewar, Central European bridge between late 19th-century realism and early modernist abstraction.

Cross-checking those signatures in Central European metalwork brought Jaroslav Vonka (also spelled “Voňka”) into focus: an orphan from Hořice who trained as a locksmith, studied evenings at Berlin’s School of Applied Arts with sculptor Fritz Klimsch, and from 1903 taught and then headed the metalwork studio at Wrocław’s Municipal School of Handicrafts and Applied Arts, where he was appointed professor in 1921. His work—gates, grilles, chandeliers, figurative elements in forged iron, and occasional freestanding figures—spans expressive and geometric idioms, mixing folklore and modernity.

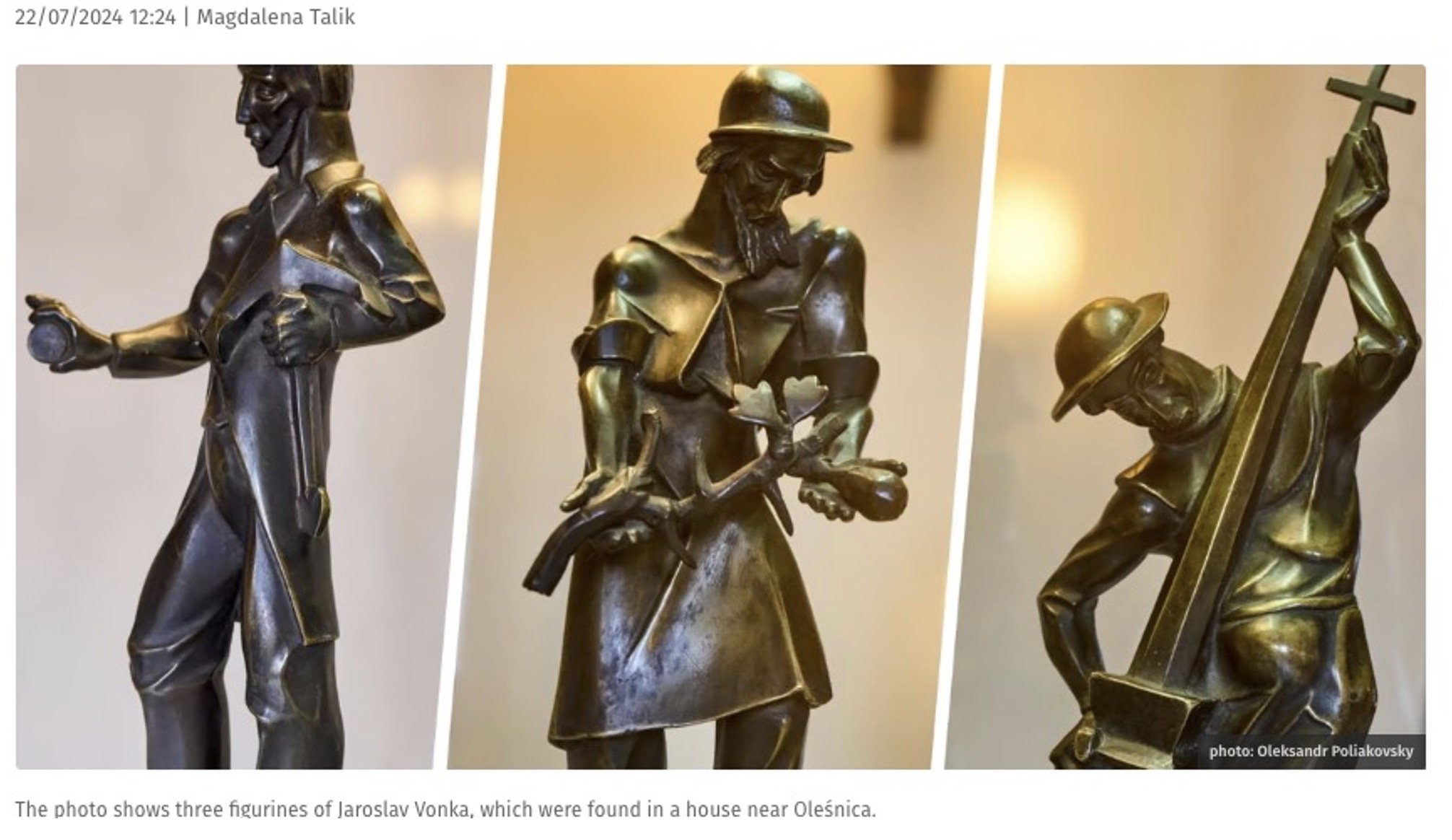

A recent public discovery helped clinch the match between our bronzes and Vonka’s hand. In 2024, three Vonka figurines were found in an attic near Oleśnica; they once adorned the modernist chandelier in the New Town Hall’s session hall (Wrocław). The city’s culture portal reported their rediscovery and installation in the Town Hall—an event that not only confirms Vonka’s authorship of closely related small bronzes but also illustrates the way his freestanding figures often originated within larger architectural or decorative ensembles.

Who Was Jaroslav Vonka?

Early Years and Formation

Born 29 March 1875 in Hořice, Vonka lost his parents early and was raised by an uncle. He completed secondary school in 1888 and apprenticed as a locksmith under a master in Miletín, receiving his journeyman’s title in 1891. Work took him through Leipzig, Dresden, Potsdam, and Berlin, where he studied in the evenings at the School of Applied Arts under Fritz Klimsch—a crucible that gave him both craft discipline and sculptural ambition.

Wrocław and the Workshop

By 1903 Vonka had accepted a post in Wrocław, leading the artistic blacksmithing workshop at the city’s applied-arts school. He earned the title professor in 1921, retired in 1937, but maintained oversight into 1943, and from 1935 lived and worked in Sobótka, a small town near Wrocław.

Signature Public Works

Vonka’s imprint is everywhere in Wrocław’s interwar fabric. Among the best documented:

Decorative metalwork for the Wrocław Hydroelectric Plants—notably the North Plant (Wrocław II, 1925), where Max Berg designed the architecture and Vonka executed the sculptural gates and metal details; the project remains a touchstone of Polish modernist industrial design.

The southern entrance wicket to Piwnica Świdnicka (1942), a unique figurative iron gate—long thought lost after the war and later recognized in a museum collection—was Vonka’s final commission for the city, featuring small allegorical figures that echo the narrative charm and stylization seen in our bronzes.

Museum attention has strengthened in recent years. The National Museum in Wrocław organized “Sculpted Wrocław” (2019–2020), a landmark survey that included Vonka among the region’s pivotal sculptors, and curated the monographic satellite “Jaroslav Vonka. Kuźnia wyobraźni” (“Forge of Imagination”) in Sobótka (2021).

Style: Between Expression and Geometry

Vonka’s idiom fuses expressionism (muscular contours, dynamic silhouettes) with Art Deco and cubist geometries (faceted planes, architectonic rhythm). The result is neither pure sculpture nor mere ornament: his figures feel forged as much as modeled, a sensibility that travels naturally between a chandelier pendant, a gate finial, and an independent statuette. Polish sources emphasize how his oeuvre “bridges decorative and fine art,” marrying folkloric themes with geometric abstraction—precisely what we see in the soldier’s segmented cuirass and in the kneeling figure’s telescoped anatomy.

Provenance: From Wrocław to Britain and North America

The two inherited bronzes come from a family whose prewar life intersected with Central Europe’s scientific and cultural elite. The great-grandfather, Heinrich August Adolf Julius Baron von Rausch von Traubenberg (1870–1944), was a physicist active in Göttingen and Prague. He appears in the Nobel Prize Nomination Archive as a nominator for Walter Gerlach and Otto Stern (Stern ultimately received the 1943 Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded in 1944). This archival record places Heinrich within the professional networks of the era and corroborates family testimony about his standing in the field.

The family’s wartime history is harrowing. Heinrich’s wife, Marie Hilde Rosenfeld Rausch von Traubenberg (1889–1964), was arrested and taken to Theresienstadt, the ghetto-labor/concentration camp used by the Nazis both as a transit hub to extermination camps and as a propaganda facade to disguise their crimes. Conditions were devastating; overcrowding, disease, and malnutrition were endemic. That she survived until liberation in 1945 aligns with the broader record of the camp’s grim functioning and the mixture of terror and manipulation the regime employed there.

In 1939, the family sent daughters Dorothee and Helen to Britain via the Kindertransport, the rescue program that brought about 10,000 predominantly Jewish children to safety in the United Kingdom—an effort coordinated by Jewish communal groups together with British charities, notably the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) through the Refugee Children’s Movement.

The girls traveled with sea chests packed with heirlooms—jewelry, silver, paintings, and statuary—one of which was stolen upon arrival in England. The remaining two chests safeguarded objects that became the core of the family collection in exile, including the Vonka bronzes. After the war, Dorothee married Wolfgang Heinrich Johannes Fuchs (1915–1997), who joined the mathematics faculty at Cornell University and spent the rest of his career there, becoming a prominent figure in complex analysis (Nevanlinna theory). The family later split the heirlooms between branches in the United States and Canada.

Finally, the family tradition preserves a human link between Heinrich Rausch von Traubenberg and Jaroslav Vonka: they knew one another, and Vonka is said to have made these figures (and printing plates) for Heinrich specifically. Given Vonka’s location and roles—Wrocław, a scientific and industrial hub; extensive work for civic institutions; ties between workshop artists and academic patrons—this commissioning relationship is stylistically and geographically plausible. The 2024 Oleśnica discovery of analogous Vonka figurines from a municipal chandelier further supports the idea that similar small bronzes circulated both in architectural contexts and as individualized casts.

Why These Bronzes Matter

1) Rarity of Freestanding Vonka Works

Vonka is celebrated primarily for architectural metalwork—gates, grilles, railings. Freestanding bronzes attributed to him, especially with secure provenance, are not common on the open market. Contemporary Polish museum programming and local scholarship have pushed his name to the forefront, but auction records in English-language databases remain sparse. The misidentification of the spyglass figure as anonymous “vintage” German bronze underscores the gap between institutional recognition and market awareness—and the opportunity for connoisseurs to acquire significant works before the market fully catches up.

2) A Clean, Documented Line

Two of the bronzes descend directly in the family from prewar Europe; the third has a paper trail through later rediscovery. The Kindertransport and subsequent Anglo-American chapter of the family’s life are not incidental details—they explain why prewar Central European bronzes survive in such pristine micro-histories today and how private heirlooms can retain scholarly significance across borders.

3) A Living Context for Vonka’s Art

The Oleśnica Town Hall rediscovery of Vonka figurines has literally restored elements of Wrocław’s prewar visual culture and placed small-scale Vonka figures back into public view. That municipal example—displayed today—provides museum-grade comparanda for the present sculptures, strengthening both their attribution and contextual reading.

Reading the Bronzes

The Soldier (c. 1925) compresses military archetype and modern form into a tight vertical: planes of armor are reduced to faceted volumes; the posture is frontal yet lively. If expressionism sought inner force and Cubism sought structural truth, Vonka’s soldier reconciles both—an artisan-sculptor’s take on modern heroism, forged rather than merely modeled.

The Companion Cubist Figure (c. 1925) hews to the same grammar: edges read like hammered arrises; volumes suggest hammered sheet swelling into relief. The architectonic feeling links it to Vonka’s gates and grilles, where human forms step out from a lattice or threshold.

The Kneeling Figure with Spyglass (c. 1920s) trades mass for narrative: a compact, horizon-scanning pose; the spyglass as a motif of vigilance and discovery. The association with chandeliers and municipal décor (via the Oleśnica example) suggests how Vonka could weave allegory into practical fittings—using miniature figures to animate urban interiors with a modern mythos.

Jaroslav Vonka’s Accomplishments, in Brief

Master craftsman & professor: Led the artistic forge at Wrocław’s applied-arts school; professor (1921); educated generations of metalworkers who disseminated his standards across Silesia.

Modern industrial ornament: Key contributor to the Wrocław hydroelectric complex (1924–25)—a showcase of how advanced engineering, architecture, and fine metalwork could form a single modernist ensemble.

Civic symbolism in iron: The Piwnica Świdnicka gate (1942), with its series of character figures, is now recognized as a late masterpiece—a work once lost, rediscovered, and newly integrated into the city’s heritage story.

Museum recognition: Featured in “Sculpted Wrocław” and the monographic “Forge of Imagination” exhibition in Sobótka (2021), which have elevated his profile for a new generation.

The Family Chronicle (Shared With Permission)

The consignor is the great-granddaughter of Heinrich A. A. J. Baron von Rausch von Traubenberg and Marie Hilde Rosenfeld Rausch von Traubenberg. The family’s account records that Marie was seized by the Gestapo and sent to Theresienstadt, where—unlike most prisoners—she was held under guard in an apartment to produce technical notes the regime believed she possessed. However unusual the circumstances, her survival until liberation is congruent with the camp’s dual reality as both a place of genuine suffering and a staged showcase designed to “sanitize” the Nazi deportation machine.

In 1939, the daughters Dorothee and Helen were placed on the Kindertransport to Britain, a rescue organized by Jewish and British humanitarian bodies including the Quakers. Their sea chests carried many family treasures—two eventually forming the backbone of the heirlooms that reached North America after Dorothee’s marriage to Wolfgang H. J. Fuchs, later a long-serving professor at Cornell University.

As for the art itself, the family maintains that Vonka and Heinrich were acquainted, and that Vonka made the figures for him, together with printing plates—entirely plausible given Vonka’s collegiate milieu in Wrocław and the Vigorous cross-pollination among artists, architects, and scientists in interwar Central Europe. The stylistic concordance with documented Vonka work and the public comparator in Oleśnica materially support that family testimony.

Collecting Significance

For museums and advanced private collectors of Central European modernism, these bronzes offer:

Documented lineage through a named émigré family tied to major historical events and academic institutions.

Scholarly resonance with recently rediscovered public works—helpful for future research and exhibition.

Market scarcity: despite museum attention, Vonka’s freestanding small bronzes rarely surface with firm attribution and provenance. (Even now, related pieces are occasionally misdescribed, as with the spyglass figure’s original online listing.)

For new audiences, they also serve as approachable ambassadors for the applied-arts tradition—an area where the boundary between “decorative” and “fine” dissolves. Vonka’s figures come from the forge, but they speak in the modern sculpture’s grammar of planes and mass.

Conclusion: Returning Names to Objects

These three bronzes—anonymous for years, misattributed in one case, and treasured quietly in another—now speak under a proper name: Jaroslav Vonka. That reclamation is not merely academic. It restores authorship, reconnects family history with civic heritage, and enlarges the story of modern European art to include the artisans who shaped its everyday grandeur—the gates we pass through, the chandeliers we look up to, and the figures that watch over us from their iron perches.

For the consignor’s family, this sale is a chapter in a longer narrative—one that began in Wrocław workshops and Göttingen laboratories, crossed the North Sea with two girls on the Kindertransport, and re-rooted itself in American academia. For collectors and curators, it is an invitation to look again at Central European metal arts—and to recognize Jaroslav Vonka as one of its decisive voices.

Sources & Further Reading

Artist & Œuvre

Exhibitions & Museum Context

- Jaroslav Vonka: “Kuźnia wyobraźni” — Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu (PL)

- Sculpted Wrocław — Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu (EN)

Oleśnica Chandelier Figurines (rediscovery)

- Figurines found near Oleśnica — wroclaw.pl (PL)

- Figurines now at the Town Hall — Nasze Miasto Oleśnica (PL)

Wrocław Public Works / Hydroelectric / City References

- City Barrage, Wrocław — Wikipedia (EN)

- Elektrownia Wodna Wrocław II — Wikipedia (PL)

- Architectus journal 39/04 — Politechnika Wrocławska (PDF)

- EW Wrocław — Tauron Ekoenergia (PL)

- Krata południowego wejścia do Piwnicy Świdnickiej — Polska-org (PL)

- ARAW Biuletyn Wrocław nr 30 (191) 2024 — wroclaw.pl (PDF, PL)

Historical Background (Theresienstadt, Kindertransport)

- Theresienstadt — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Kindertransport (1938–40) — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Kindertransport — Quakers in Britain

Family & Academic References

Note on claims: Where the article reports family testimony (e.g., the personal connection between Vonka and Heinrich Rausch von Traubenberg, and the bespoke origin of the figures), it is identified as such. The stylistic match, documented career arc, and recent municipal rediscoveries in Wrocław provide independent context that makes this family account historically and artistically credible.

Written by Michael Fallon